Links to Ron's Workshop Materials

- Music to 'Cover'

Conversations

- Appointment Clock (Learning Partners)

- Fine Feathered Friends (Learning Partners)

- Tunes Listing

- Directions for OPIN

- Directions for Paired Verbal Fluency

- Directions for Word Splash

- Creating Cued Music with iTunes (Courtesy of Angel Bonham)

- Spelling Grid Explanation

- Eddie

Classroom Tips from Ron

A building principal once asked me, “What do I recommend to teachers as a place to start when they want to insert student-to-student conversations into their lesson plans?” I told him to have his teachers begin with paired conversations (seated or standing).

Why begin with pairs, rather than trios or quartets?

- Students are less inhibited in dialogue mode when they have to deal with a single partner, rather than a larger group. There is no place to hide in a pair. A single student can become virtually invisible in a quartet or an even larger group, but not if that one partner is relying on his cooperation and support.

- Students can more easily practice speaking and listening skills in pairs, and teachers can more easily listen in on the conversations.

- Students get more practice in pairs, for the simple reason that if a teacher has 30 students in the room, there can be 15 conversations going on simultaneously.

I recommend standing pairs at least half the time in the classroom. Almost any conversations that can take place while seated can occur while standing with that same partner or with many different partners over the course of several minutes. Movement sends oxygen and glucose to the brain, and it releases neurotransmitters critical for thought.

The very first few paired conversations should deal with personal topics such as the following:

- What would you do with a 100% free summer day?

- Discuss your favorite movie genres, along with your favorite movies within those categories?

- What is your idea of a perfect week-long vacation?

- Discuss the attributes of a good friend?

Once students feel comfortable having the conversations with different partners, you can work in content-related topics and concepts.

It is also easy to move students from pairs into quartets (sometimes called pairs squared) for various tasks.

So, begin with seated and standing pair shares, then move on from there.

Personal or group reflection is a powerful tool. At the end of the nine weeks, for example, teachers can pause and reflect on that first quarter of the school year, asking themselves the following questions:

During the past nine-week grading period, did I…

- Provide opportunities for student-to-student conversations that allowed them to work in the comprehension level of Bloom?

- Break my class periods or blocks into eight- or ten-minute segments that permitted my students to alternately stand, move, and sit?

- Get my students up for a minute of exercises that will release serotonin, dopamine, and other neurotransmitters?

- Work into my plans opportunities for student-to-student conversations, or discussions in trios or small groups?

- Provide a few minutes of student processing following a short lecture or video?

These five tips are important components in the continuous-improvement journeys of students of any age.

The most effective teachers I have observed over the past two decades incorporate movement, student-to-student discussion, and frequent physical and mental state changes into their lessons.

Take a look at next week’s lessons on Friday afternoon or Saturday morning. Are there places where what has to be done can be done standing, in pairs or trios, or in groups of four or five?

When I plan my workshops, I build several ten-minute segments into the lesson plan. That is, I alternate between seated segments and those during which participants are standing and sharing. I always ask my workshop participants if they have ever been in a night class where, after 10 or 15 minutes, they have gone to “a better place in their minds.” Almost every hand goes up, and it tells me that we as adults need to move and change our physical state after a short time.

The same is true of students, and the younger the student the shorter the time span before they get “antsy” or “fidgety,” even if they are NOT diagnosed with ADHD. Adults, adolescents, and children gotta move, and teachers need to build movement into their lesson plans. In one sixth-grade middle school classroom I visited, the students were up and down in roughly eight-minute segments over a 55 –minute language arts class period. Those sixth graders were engaged the whole time, and music accompanied every move and every conversation or visit to a chart on the wall.

Teachers can take their lesson plans—no matter the subject—and decide what can be accomplished with students who are standing and paired or grouped with classmates. The simple act of standing up sends 15% more blood to the brain—blood that carries oxygen and glucose (for energy).

Here is what I have found in four decades in education: Kids who are not given opportunities to move in a structured way will find ways to move on their own (going to the pencil sharpener when the pencil is already sharp, asking to go to the restroom, taking something to the wastebasket, or talking to a neighbor). In classrooms where teachers provide the movement as a matter of course, students don’t generally DO all these other things in an attempt to move—the teacher provides the movement.

Build into your lesson plans opportunities for movement in the name of learning.

Oral language skills are closely tied to reading and writing skills, and the best way for students to get a workout in the second level of Bloom (comprehension) is to have them explain something to another student, discuss something with another student, and summarize something another student has said. Many students feel much more comfortable talking with another student than they do when they are faced with sharing with the entire class.

These conversations can be structured so that each student in a pair gets to explain something, while the other follows that explanation with an opportunity to summarize. This is called Paired Verbal Fluency (PVF), and the directions are on this website under Free Stuff.

Another iteration of PVF is when Eddie talks, followed by Fred continuing to talk about that same topic without repeating what Eddie said. You might, for example, have Partner A explain what it takes to be a good listener, followed by B (on your signal) continuing to explain without repeating.

Either way (summarizing or continuing to talk without repeating), the listener has to really listen in order to carry out his or her task when the speaker is done. the teacher’s job is to walk around the room, monitoring the conversations and looking for one or two students who may be willing to share what they discussed in the pairs.

When working with students, I have Partner A talk for maybe 20 seconds or so, followed by another 20 seconds for B. The first thing they discuss should be something with which they are perfectly familiar (great vacations, great music, favorite leisure activities). THEN you can have them move onto content-laden topics. This can, by the way, make a great review activity.

The power here is that at any one time, half the kids are talking and half are listening prior to completing their own task (summarizing, etc.). He or she who does the talking does the learning. Give them their 80.

In typical room arrangements in schools all over the country, straight rows of desks predominate. These arrangements tend to do two things when it comes to movement: 1) It is often difficult for teachers to move around quickly and efficiently, due to the barriers created by the rows, and 2) It is often difficult or impossible for students to stand and meet in pairs, trios, or quartets.

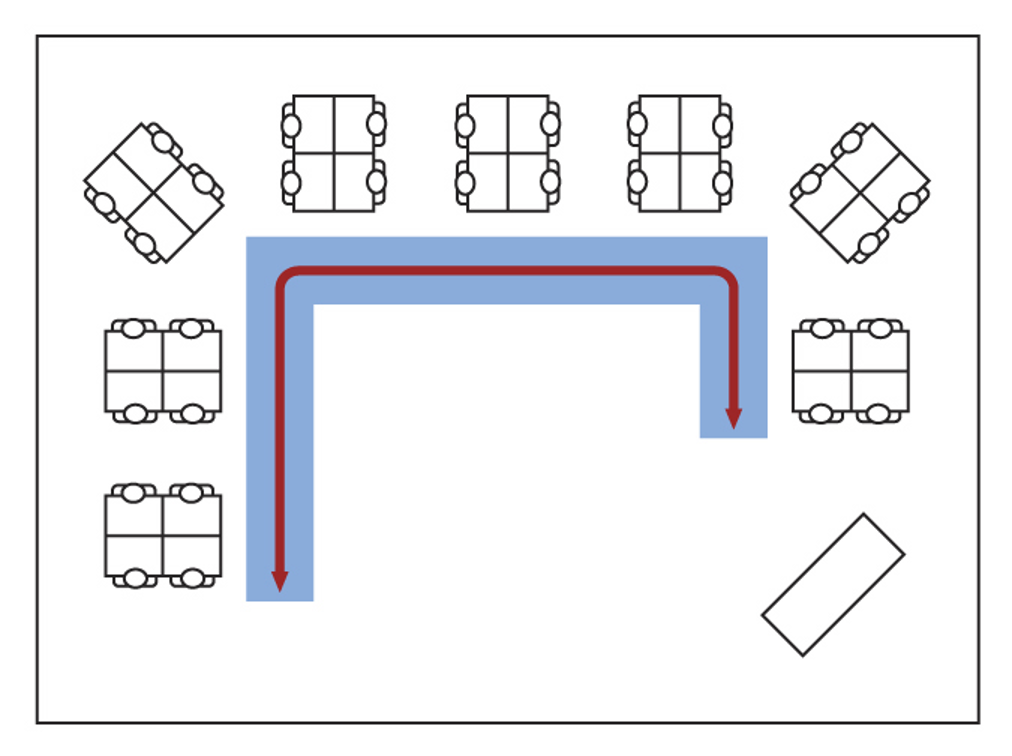

The perimeter furniture arrangement to the left opens up a large space in the center of the room, so that students can easily move into that area without a great deal of confusion, and with no furniture barring the way. Notice, too, that when students are seated, the teacher has a wide-open avenue of movement (marked by the red line and arrow) where he or she is never more than one person away from any student in the room. When students are doing seatwork, teachers can move around at will, helping students without any obstacles.

Another advantage of this room arrangement is that students can, while doing seatwork, meet with a “face partner” or “shoulder partner” without having to move chairs or desks.

Finally, when the teacher is front and center in the classroom, no student has to do more than turn his or her chair slightly in order to make eye contact with the teacher, while still being able to take notes or reference a book or other resource on the desk. Moving slightly gives them a clear line of sight to the screen.

He who does the talking does the learning, which is why I learned more about American history in my first year of teaching than I did in all my years of undergraduate and graduate work. This is because I did the talking. When students talk, they learn, and the room arrangement in the attached file allows for students to meet, discuss something, process information—while the teacher walks among the pairs listening to the conversations, and deciding who she will have share out during the debriefing.

You might take a look at your current classroom furniture arrangement with an eye toward making some changes that will facilitate student movement and structured conversations.